|

|

Maritime

Lanka |

19 Nov2003

|

|||

| Last modified: 19 Nov2003 |

'Pilots'

for the relevant routes were given to VOC captains before each voyage. These

instructions contained detailed information about navigation, winds and currents,

and directions for approaching and entering harbours. The skippers themselves

kept notes in their ships' logs, which were fed back to the compilers to improve

and update the pilots.

'Pilots'

for the relevant routes were given to VOC captains before each voyage. These

instructions contained detailed information about navigation, winds and currents,

and directions for approaching and entering harbours. The skippers themselves

kept notes in their ships' logs, which were fed back to the compilers to improve

and update the pilots.

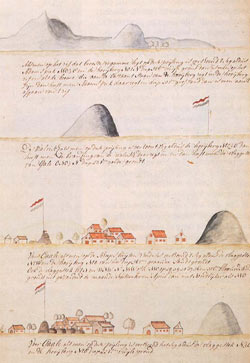

For example, in the drawings and notes of captain Schilde and skipper Hoogendorp, made in 1757, the approach to Galle Harbour is described from various directions. The flagstaff and two mountains (Adam's Peak and the ‘Hooiberg’ Hay Cock) were important landmarks. The first two drawings show landmarks which would indicate the ship is in a dangerous position to approach the bay. The other drawings show the view when a ship is on a safe course towards the entrance of the bay.

In the following view of Galle from the flagstaff, one can see in the background the two mountains used by navigators. In the city, one can see from left to right the Dutch reformed church, the warehouse, the Black Fort, and the location of the harbour behind the palm trees.

|

|

Although the internal harbour of Galle was considered safe during most of the year, the entrance of the harbour was not. Reefs and submerged cliffs were a danger to the ships. To enter the bay safely, skippers needed the services of a local pilot. (The word 'pilot' is used both for the local expert and for the navigation manual carried on board.)

While ships were at anchor outside the bay, they could communicate with the shore with flags and guns. If the skipper required a pilot, a Dutch flag was hung on the mizzen yard and a gun fired three times. The flagstaff guard would indicate that the signal was understood by hanging the Dutch flag upside down.

Local dhoni were used to bring the pilot to the ships and then to guide the ships into the harbour. In the first of the prints on the right, a dhoni is sailing in front of the Dutch ship. In the second, a ship has come safely to anchor near the Black Fort.

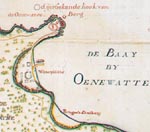

When

ships were piloted into the harbour, it was common practice to anchor small

dhoni as temporary buoys on the most dangerous spots, shown on this 17th century

map.

When

ships were piloted into the harbour, it was common practice to anchor small

dhoni as temporary buoys on the most dangerous spots, shown on this 17th century

map.

|

|

|

|

Ships were unloaded, revictualled and loaded by smaller boats which operated from the jetties near the old town gate. A map from 1660 shows only one jetty, which would presumably have been where the Avondster loaded her cargo; by the 19th century there were separate jetties for import, export, supplies, etc. One of these jetties has recently been converted to serve as the diving base and conservation laboratory for the Maritime Archaeology Unit. Just inside the gate is the great warehouse, now the Maritime Museum. Galle also had a small shipyard and skilled craftsmen, who could carry out necessary ship repairs.

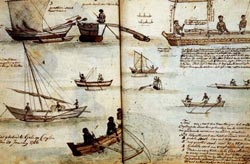

The variety of small vessels in service in the Bay of Galle is shown in the sketch on the right by an eighteenth century traveller.

Drinking water came from the watering place on the eastern side of the bay. The diagram on the left shows how this was organised, with multiple pipes and a jetty. Water was carried in barrels to the town and the ships. The water for the town was carried through a tunnel into the Black Fort (Schwartz Bastion). The tunnel still exists, but is sealed since it leads into police headquarters. The picture on the right shows the boats used to carry water to the ships.

| Maritime Lanka homepage | The Hercules, 1661 |